Check the link for all the winners. http://ibloga.blogspot.com/

"David and Mohammed."

The Iranian newspaper that launched an international cartoon contest about the Holocaust as retaliation for the satirical drawings insulted of Mohammed will go through "a test of freedom of expression."

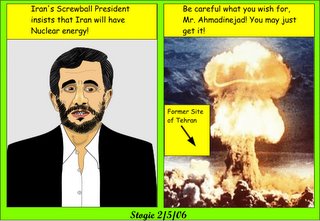

A Portuguese artist will take part in the contest of the Iranian paper Hamshahri with a caricature ridiculing Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmedinajad. He is drawn as visiting a museum in the well-known concentration camp Auschwitz and says the only explanation to the deaths in this summer camp is bird flu.

The caricaturist, Augusto Cid, said he does not know whether his work "suits the spirit of the contest," but the real reason he will participate will be "to test the freedom of expression in Iran."

In the meantime, the organization of Journalists with No Boundaries asked the release of the seven journalists from Algeria, Syria, and Yemen who are still under arrest for publishing the cartoons. In Russia, a newspaper published in Volgograd was closed down for publishing cartoons of the three monotheistic religions and Buddha.

http://www.deviantart.com/view/29251256/.

http://www.deviantart.com/view/29251256/.

.

.

He was behind the push to impose Shari'a onto Canadians in Ontario, and he promotes murder and mayhem against civilians, but whoa, don't upset the man by publishing cartoons of Mohammed, murder and child molestor prophet of the fascist poligion that is Islam. He might cut off your head. This terrorist arsehole now wants to sue a publisher in Canada. What next? Well, likely he'll murder somone. He is a terrorist.

He was behind the push to impose Shari'a onto Canadians in Ontario, and he promotes murder and mayhem against civilians, but whoa, don't upset the man by publishing cartoons of Mohammed, murder and child molestor prophet of the fascist poligion that is Islam. He might cut off your head. This terrorist arsehole now wants to sue a publisher in Canada. What next? Well, likely he'll murder somone. He is a terrorist.He said the cartoons propagate a negative stereotype of Muslims, and the decision to publish them goes against the will of the Canadian people and "actually affects the well being of minorities in this country."

Elmasry also said the Muslim people have been unfairly targeted, and said he believes the magazine would have acted differently if the cartoons were anti-Semitic.

Muslim leader accuses Cdn publisher of hate crimeIt is with sadness that we note the passing of our friend Roger Shattuck, teacher, poet, essayist, and literary observer par excellence. Roger was the sort of man-of-letters one reads about but scarcely encounters any more: literary to his fingertips, but graced with manly common-sense and instinctive independence of mind: a gentleman in the highest sense of that retired epithet. Roger was never part of any school or clique or movement. He regarded fads like deconstruction with amused distaste: something to hold one's nose about while disposing of it quickly and with as little comment as possible. His most famous book, in some ways his best, was also his first: The Banquet Years: The Origins of the Avant-Garde in France, 1885 to World War I (1958), a quirky, seductive, utterly original romp through the work of Henri Rousseau, Alfred Jarry, Erik Satie, and Guillaume Apollinaire. Roger made connections—made sense—out of themes and continuities that no one had sensed before but that now seem obvious. Roger's mind was omnivorous, as at home in anthropology and moral philosophy as it was in literature. He wrote on Proust; on "the Wild Boy of Aveyron," the feral child discovered in France in the nineteenth century; and all manner of literary controversy and incident.

One of Roger's most thoughtful and ambitious (and by accident most contentious) books was Forbidden Knowledge: From Prometheus to Pornography (1996), which began with the arresting question: "Are there things we should not know?" Today, shallow intellectuals bandy about words like "subversive" and "transgressive" as terms of endearment. But the age-old uneasiness about the subversive potentialities of unfettered knowledge reveal a recognition that knowledge can bring unhappiness and ruin as well as insight and liberation. This thought is embedded in countless myths and stories, many of which Roger anatomizes in the course of his book.

Since the Enlightenment, it has been increasingly difficult for us in the West to give much credence to or even properly to understand the kind of moral-religious criticism that Augustine (for example) mounts against unfettered curiosity. We are increasingly secular creatures who rankle at the very prospect of there being "limits" to knowledge, let alone ones prescribed by any human agency. It is one of Mr. Shattuck's most impressive achievements to have been able to bring readers back behind this Enlightenment assumption and reanimate the kinds of questions posed by Augustine and the many authors he discusses, from Homer and Aeschylus to Milton, Melville, Montaigne, and Molière. In the "applications" part of his book, Roger concentrates on three cases studies: the decision to build and use the atomic bomb in World War II; the human genome project and the prospect of genetic engineering; and the question of whether certain extreme forms of pornography (the Marquis de Sade furnishes his chief text) ought to be controlled. Where do we find the authority to say the limit should be just here? Or here? Or here? There are no simple answers to the urgent quandaries that Mr. Shattuck illuminates in this impressive study. We must be grateful to him for bringing the questions to life once more. As the eighteenth-century aphorist G. C. Lichtenberg once observed, "Today we are trying to spread knowledge everywhere. Who knows if in centuries to come there will not be universities for re-establishing our former ignorance?"

Since the Enlightenment, it has been increasingly difficult for us in the West to give much credence to or even properly to understand the kind of moral-religious criticism that Augustine (for example) mounts against unfettered curiosity. We are increasingly secular creatures who rankle at the very prospect of there being "limits" to knowledge, let alone ones prescribed by any human agency. It is one of Mr. Shattuck's most impressive achievements to have been able to bring readers back behind this Enlightenment assumption and reanimate the kinds of questions posed by Augustine and the many authors he discusses, from Homer and Aeschylus to Milton, Melville, Montaigne, and Molière. In the "applications" part of his book, Roger concentrates on three cases studies: the decision to build and use the atomic bomb in World War II; the human genome project and the prospect of genetic engineering; and the question of whether certain extreme forms of pornography (the Marquis de Sade furnishes his chief text) ought to be controlled. Where do we find the authority to say the limit should be just here? Or here? Or here? There are no simple answers to the urgent quandaries that Mr. Shattuck illuminates in this impressive study. We must be grateful to him for bringing the questions to life once more. As the eighteenth-century aphorist G. C. Lichtenberg once observed, "Today we are trying to spread knowledge everywhere. Who knows if in centuries to come there will not be universities for re-establishing our former ignorance?"