The West, particularly France

The West, particularly France, is in a state of self-induced nausea in the Sartrean sense. Between the sentimentalising of culture at its lowest possible levels and the corruption of intellectual standards at the highest and with a sludge-making of the middle the European populations and many of the West generally are sick of themselves and of Modernity. Scum people rise to the top of the social pond by virtue of the mass of middle-class people foolishly and outrageously promoting the interests of those who would harm all. This incredible stupidity on the part of the Western masses destroys those it's perhaps meant to help, i.e. the scum people, and then destroys the rest of society by letting the scum seep into the fabric of life over-all.

We can go on, but let's not.

The following pieces give weight and definition to the term philobarbarism, and Left dhimmi fascism, as if anything further were needed.

Alain Finkielkraut. "When an Arab torches a school, it's rebellion. When a white guy does it, it's fascism. I'm 'color blind.' Evil is evil, no matter what color it is. And this evil, for the Jew that I am, is completely intolerable." (Hannah/Opale)

What sort of Frenchmen are they?

By Dror Mishani and Aurelia Smotriez

PARIS - The first thing the French-Jewish philosopher Alain Finkielkraut said to us when we met one evening at Paris' elegant Le Rostand cafe, where the interior is decorated with Oriental-style pictures and the terrace faces the Luxembourg Gardens, was "I heard that even Haaretz published an article identifying with the riots."

This remark, uttered with some vehemence, pretty much sums up the feelings of Finkielkraut - one of the most prominent philosophers in France in the past 30 years - ever since the violent riots began on October 27 in the impoverished neighborhoods that surround Paris and spread with surprising speed to similar suburbs throughout the country. He has been following the events through the media, keeping up with all the news reports and commentary, and has been appalled at every article that shows understanding for or identification with "the rebels" (and in the French press, there are plenty). He has a lot to say, but it appears that France isn't ready to listen - that his France has already surrendered to a blinding, "false discourse" that conceals the stark truth of its situation. The things he is saying to us in the course of our conversation, he repeatedly emphasizes, are not things he can say in France anymore. It's impossible, perhaps even dangerous, to say these things in France now.

Indeed, in the lively intellectual debate that has been taking place on the pages of the French newspapers ever since the rioting started, a debate in which France's most illustrious minds are taking part, Finkielkraut's is a deviant, even very deviant, voice. Primarily because it is not emanating from the throat of a member of Jean Marie Le Pen's National Front, but from that of a philosopher formerly considered to be one of the most eminent spokesmen of the French left - one of the generation of philosophers who emerged at the time of the May 1968 student revolt.

In the French press, the riots in the suburbs are perceived mainly as an economic problem, as a violent reaction to severe economic hardship and discrimination. In Israel, by comparison, there is sometimes a tendency to view them as violence whose origins are religious or at least ethnic - that is, to see them as part of an Islamic struggle. Where would you situate yourself in respect to these positions?

Finkielkraut: "In France, they would like very much to reduce these riots to their social dimension, to see them as a revolt of youths from the suburbs against their situation, against the discriminationunemployment. The problem is that most of these youths are blacks or Arabs, with a Muslim identity. Look, in France there are also other immigrants whose situation is difficult - Chinese, Vietnamese, Portuguese - and they're not taking part in the riots. Therefore, it is clear that this is a revolt with an ethno-religious character. they suffer from, against the

"What is its origin? Is this the response of the Arabs and blacks to the racism of which they are victims? I don't believe so, because this violence had very troubling precursors, which cannot be reduced to an unalloyed reaction to French racism.

"Let's take, for example, the incidents at the soccer match between France and Algeria that was held a few years ago. The match took place in Paris, at the Stade de France. People say the French national team is admired by all because it is black-blanc-beur ["black-white-Arab" - a reference to the colors on France's tricolor flag and a symbol of the multiculturalism of French society - D.M.]. Actually, the national team today is black-black-black, which arouses ridicule throughout Europe. If you point this out in France, they'll put you in jail, but it's interesting nevertheless that the French national soccer team is composed almost exclusively of black players.

"Anyway, this team is perceived as a symbol of an open, multiethnic society and so on. The crowd in the stadium, young people of Algerian descent, booed this team throughout the whole game! They also booed during the playing of the national anthem, the `Marseillaise,' and the match was halted when the youths broke onto the field with Algerian flags.

"And then there are the lyrics of the rap songs. Very troubling lyrics. A real call to revolt. There's one called Dr. R., I think, who sings: `I piss on France, I piss on De Gaulle' and so on. These are very violent declarations of hatred for France. All of this hatred and violence is now coming out in the riots. To see them as a response to French racism is to be blind to a broader hatred: the hatred for the West, which is deemed guilty of all crimes. France is being exposed to this now."

In other words, as you see it, the riots aren't directed at France, but at the entire West?

"No, they are directed against France as a former colonial power, against France as a European country. Against France, with its Christian or Judeo-Christian tradition."

`Anti-republican pogrom'

Alain Finkielkraut, 56, has come a long way from the events of May 1968 to the riots of October 2005. A graduate of one of the chief breeding grounds for French intellectuals, the Ecole Normal Superieure, in the early 1970s, Finkielkraut was identified with a group known as "the new philosophers" (Bernard Henri-Levy, Andre Glucksman, Pascal Bruckner and others) - young philosophers, many of them Jewish, who made a critical break with the Marxist ideology of May 1968 and with the French Communist Party, and denounced its impact on French culture and society.

In 1987, he published his book "The Defeat of the Mind," in which he outlined his opposition to post- modernist philosophy, with its erasure of the boundaries between high and low culture and its cultural relativism. And thus he began to earn a name as a "conservative" philosopher and scathing critic of the multicultural and post-colonial intellectual currents, as someone who preached a return to France's republican values. Finkielkraut was one of the staunchest defenders of the controversial law prohibiting head-coverings in schools, which has roiled France in recent years.

Over time, he also became a symbol of the "involved intellectual," as exemplified by the postwar Jean-Paul Sartre - a philosopher who doesn't abstain from participation in political life, but instead writes in the newspapers, gives interviews and devotes himself to humanitarian causes such as halting the ethnic cleansing in Bosnia or the slaughter in Rwanda. The danger he wishes to stand up to today, in light of the riots, is the growing hatred for the West and its penetration into the French education system.

Do you think that the source of the hatred for the West among the French who are taking part in the riots lies in religion, in Islam?

"We need to be clear on this. This is a very difficult question and we must strive to maintain the language of truth. We tend to fear the language of truth, for `noble' reasons. We prefer to say the `youths' instead of `blacks' or `Arabs.' But the truth cannot be sacrificed, no matter how noble the reasons. And, of course, we also must avoid generalizations: This isn't about blacks and Arabs as a whole, but about some blacks and Arabs. And, of course, religion - not as religion, but as an anchor of identity, if you will - plays a part. Religion as it appears on the Internet, on the Arab television stations, serves as an anchor of identity for some of these youths.

"Unlike others, I have not spoken about an `intifada' of the suburbs, and I don't think this lexicon ought to be used. But I have found that they are also sending the youngest people to the front lines of the struggle. You've seen this in Israel - they send the youngest ones to the front because it's impossible to put them in jail when they're arrested. But still, here there are no bombings and we're in a different stage: I think it's the stage of the anti-republican pogrom. There are people in France who hate France as a republic."

But why? For what reason?

"Why have parts of the Muslim-Arab world declared war on the West? The republic is the French version of Europe. They, and those who justify them, say that it derives from the colonial breakdown. Okay, but one mustn't forget that the integration of the Arab workers in France during the time of colonial rule was much easier. In other words, this is belated hatred. Retrospective hatred.

"We are witness to an Islamic radicalization that must be explained in its entirety before we get to the French case, to a culture that, instead of dealing with its problems, searches for an external guilty party. It's easier to find an external guilty party. It's tempting to tell yourself that in France you're neglected, and to say, `Gimme, gimme.' It hasn't worked like that for anyone. It can't work."

Post-colonial mindset

But what appears to disturb Finkielkraut even more than this "hatred for the West," is what he sees as its internalization in the French education system, and the identification with it by French intellectuals. In his view, this identification and internalization - which are expressed in shows of understanding for the sources of the violence and in the post-colonial mindset that is permeating the education system - are threatening not only France as a whole, but the country's Jews, too, because they are creating an infrastructure for the new anti-Semitism.

"In the United States, too, we're witnessing an Islamization of the blacks. It was Louis Farrakhan, in America, who asserted for the first time that the Jews played a central role in creating slavery. And the main spokesman for this theology in France today is Dieudonne [a black stand-up artist, who caused an uproar with his anti-Semitic statements - D.M.]. Today he is the true patron of anti-Semitism in France, and not Le Pen's National Front.

"But in France, instead of fighting his kind of talk, they're actually doing what he asks: changing the teaching of colonial history and the history of slavery in the schools. Now they teach colonial history as an exclusively negative history. We don't teach anymore that the colonial project also sought to educate, to bring civilization to the savages. They only talk about it as an attempt at exploitation, domination and plunder.

"But what does Dieudonne really want? He wants a `Holocaust' for Arabs and blacks, too. But if you want to put the Holocaust and slavery on the same plane, then you have to lie. Because [slavery] wasn't a Holocaust. And [the Holocaust] wasn't `a crime against humanity,' because it wasn't just a crime. It was something ambivalent. The same is true of slavery. It began long before the West. In fact, what sets the West apart when it comes to slavery is that it was the one to eliminate it. The elimination of slavery is a European and American thing. But this truth about slavery cannot be taught in schools.

"That's why these events sadden me so greatly; not so much because they happened. After all, you'd have to be deaf and blind not to see that they would happen. But because of the interpretations that have accompanied them. These dealt a decisive blow to the France I loved. And I've always said that life will become impossible for Jews in France when Francophobia triumphs. And that's what will happen. The Jews understand what I've said just now. Suddenly, they look around, and they see all the `bobo' (French slang for bourgeois-bohemians) singing songs of praise to the new `wretched of the earth' [Finkielkraut is alluding here to the book by the Martinique-born, anti-colonialist philosopher Franz Fanon - D.M.] and asking themselves: What is this country? What's happened to it?"

Since you view this as an Islamic assault, how do you explain the fact that Jews have not been attacked in the recent events?

"First of all, they say that one synagogue has been attacked. But I think that what we've experienced is an anti-republican pogrom. They tell us that these neighborhoods are neglected and the people are in distress. What connection is there between poverty and despair, and wreaking destruction and setting fire to schools? I don't think any Jew would ever do a thing like this."

Horrifying acts

Finkielkraut continues: "What unites the Jews - the secular, the religious, the Peace Now crowd, the Greater Land of Israel crowd - is one word: shul (synagogue; used here as religious study hall). That's what holds us all together as Jews. And I have been just horrified by these acts, which kept repeating themselves, and horrified even more by the understanding with which they were received in France. These people were treated like rebels, like revolutionaries. This is the worst thing that could happen to my country. And I'm very miserable because of it. Why? Because the only way to overcome it is to make them feel ashamed. Shame is the starting point of ethics. But instead of making them feel ashamed, we gave them legitimacy. They're `interesting.' They're `the wretched of the earth.'

"Imagine for a moment that they were whites, like in Rostock in Germany. Right away, everyone would have said: `Fascism won't be tolerated.' When an Arab torches a school, it's rebellion. When a white guy does it, it's fascism. I'm `color blind.' Evil is evil, no matter what color it is. And this evil, for the Jew that I am, is completely intolerable.

"Moreover, there's a contradiction here. Because if these suburbs were truly in a state of total neglect, there wouldn't be any gymnasiums to torch, there wouldn't be schools and buses. If there are gymnasiums and schools and buses, it's because someone made an effort. Maybe not enough of one, but an effort."

Still, the unemployment rate in the suburbs is very extreme: Almost 40 percent of young people aged 15-25 have no chance of finding a job.

"Let's return to the shul for a moment. When parents send you to school, is it in order for you to find a job? I was sent to school in order to learn. Culture and education have a justification per se. You go to school to learn. That is the purpose of school. And these people who are destroying schools - what are they really saying? Their message is not a cry for help or a demand for more schools or better schools. It's a desire to eliminate the intermediaries that stand between them and their objects of desire. And what are their objects of desire? Simple: money, designer labels, sometimes girls. And this is something for which our society surely bears responsibility. Because they want everything immediately, and what they want is only the consumer-society ideal. It's what they see on television."

Declaration of war

Finkielkraut, as his name indicates, is himself the child of an immigrant family: His parents came to France from Poland; their parents perished at Auschwitz. In recent years, his Judaism has become a central theme in his writing, too, especially since the start of the second intifada and the rise in anti-Semitism in France. He is one of the leaders of the struggle against anti-Semitism in France, and also one of the most prominent supporters of Israel and its policies, in the face of Israel's many critics in France.

His standing as a key spokesperson within the Jewish community in France has grown, particularly since he began hosting a weekly talk show on the JCR Jewish radio station, one of four Jewish stations in the country. On this program, Finkielkraut discusses current events; for the past two weeks, the riots in the suburbs were naturally the main topic. Because of his standing as one of the most widely heard Jewish intellectuals within France's Jewish community, his perspective on the events will certainly have an influence on the way in which they are perceived and understood among French Jewry - and perhaps also on the future of the relationship between the Jewish and Muslim communities. But this Jewish philosopher and tenacious fighter of anti-Semitism is using these latest events to declare war - on the "war on racism."

"I was born in Paris, but I'm the son of Polish immigrants. My father was deported from France. His parents were deported and murdered in Auschwitz. My father returned from Auschwitz to France. This country deserves our hatred: What it did to my parents was much more violent than what it did to Africans. What did it do to Africans? It did only good. It put my father in hell for five years. And I was never brought up to hate. And today, this hatred that the blacks have is even greater than that of the Arabs."

But do you, of all people, who fight against anti-Jewish racism, maintain that the discrimination and racism these youths are talking about doesn't actually exist?

"Of course discrimination exists. And certainly there are French racists. French people who don't like Arabs and blacks. And they'll like them even less now, when they know how much they're hated by them. So this discrimination will only increase, in terms of housing and work, too.

"But imagine that you're running a restaurant, and you're anti-racist, and you think that all people are equal, and you're also Jewish. In other words, talking about inequality between the races is a problem for you. And let's say that a young man from the suburbs comes in who wants to be a waiter. He talks the talk of the suburbs. You won't hire him for the job. It's very simple. You won't hire him because it's impossible. He has to represent you and that requires discipline and manners, and a certain way of speaking. And I can tell you that French whites who are imitating the code of behavior of the suburbs - and there is such a thing - will run into the same exact problem. The only way to fight discrimination is to restore the requirements, the educational seriousness. This is the only way. But you're not allowed to say that, either. I can't. It's common sense, but they prefer to propound the myth of `French racism.' It's not right.

"We live today in an environment of a `perpetual war on racism' and the nature of this anti-racism also needs to be examined. Earlier, I heard someone on the radio who was opposed to Interior Minister Sarkozy's decision to expel anyone who doesn't have French citizenship and takes part in the riots and is arrested. And what did he say? That this was `ethnic cleansing.' During the war in Yugoslavia I fought against the ethnic cleansing of Muslims in Bosnia. Not a single French Muslim organization stood by our side. They bestirred themselves solely to support the Palestinians. And to talk about `ethnic cleansing' now? There was a single person killed in the riots. Actually, there were two [more], but it was an accident. They weren't being chased, but they fled to an electrical transformer even though the warning signs on it were huge.

"But I think that the lofty idea of `the war on racism' is gradually turning into a hideously false ideology. And this anti-racism will be for the 21st century what communism was for the 20th century. A source of violence. Today, Jews are attacked in the name of anti-racist discourse: the separation fence, `Zionism is racism.'

"It's the same thing in France. One must be wary of the `anti-racist' ideology. Of course, there is a problem of discrimination. There's a xenophobic reflex, that's true, but the portrayal of events as a response to French racism is totally false. Totally false."

And what do you think about the steps the French government has taken to quell the violence? The state of emergency, the curfew?

"This is so normal. What we have experienced is terrible. You have to understand that the ones who have the least power in a society are the authorities, the rulers. Yes, they are responsible for maintaining order. And this is important because without them, some sort of self-defense would be organized and people would shoot. So they're maintaining order, and doing it with extraordinary caution. They should be saluted.

"In May 1968 there was a totally innocent movement compared to the one we're seeing now, and there was violence on the part of the police. Here they're tossing Molotov cocktails, firing live bullets. And there hasn't been a single incident of police violence. [Since this interview, several police officers have been arrested on suspicion of using violence - D.M.] There's no precedent for this. How to impose order? By using `common sense' methods, which by the way, according to a poll by La Parisienne newspaper, 73 percent of the French support.

"But apparently it's already too late to make them feel ashamed, since on the radio, on television and in the newspapers, or in most of them, they're holding a prettifying mirror up to the rioters. They're `interesting' people, they're nurturing their suffering and they understand their despair. In addition, there's the great perversion of the spectacle: They're burning cars in order to see it on television. It makes them feel `important' - that they live in an `important neighborhood.' The pursuit of this spectacle ought to be analyzed. It's creating totally perverted effects. And the perversion of the spectacle is accompanied by totally perverted analyses."

Failed models

Since the start of the riots in the suburbs, the press throughout Europe has been addressing the issue of multiculturalism, its possibilities and its costs. Finkielkraut expressed his opinion on this question, which is also occupying the minds of many writers in Israel, many years ago when he came to the defense of the republican model and its symbol, the republican school, against the intellectual currents that sought to open French society and its education system to the cultural variety brought in by the immigrants. While many intellectuals perceive the latest events as deriving from insufficient openness to the "other," Finkielkraut actually sees them as proof that cultural openness is doomed to end in disaster.

"They're saying that the republican model has collapsed in these riots. But the multicultural model isn't in any better shape. Not in Holland or in England. In Bradford and Birmingham there were riots with an ethnic background, too. And, secondly, the republican school, the symbol of the republican model, hasn't existed for a long time already. I know the republican school; I studied in it. It was an institution with strict demands, a bleak, unpleasant place that built high walls to keep out the noise from outside. Thirty years of foolish reforms have altered our landscape. The republican school has been replaced by an `educational community' that is horizontal rather than vertical. The curricula have been made easier, the noise from outside has come in, society has come inside the school.

"This means that what we're seeing today is actually the failure of the `nice' post-republican model. But the problem with this model is that it is fueled by its own failures: Every fiasco is a reason to become even more extreme. The school will become even `nicer.' When really, given what we're seeing, greater strictness and more exacting standards are the minimum that we need to ask for. If not, before long we'll have `courses in crime.'

"This is an evolution that characterizes democracy. Democracy, as a process, and Tocqueville showed this, does not abide selfishness. Within democracy, it's hard to tolerate non-democratic spaces. Everything has to be done democratically in a democracy, but school cannot be this way. It just can't. The asymmetry is glaring: between he who knows and he who doesn't know, between he who brings a world with him and he who is new in this world.

"The democratic process delegitimizes this asymmetry. It's a general process in the Western world, but in France it takes a more pathetic form, because one of the things that characterizes France is its strict education. France was built around its schools."

Many of the youths say the problem is that they don't feel French, that France doesn't really regard them as French.

"The problem is that they need to regard themselves as French. If the immigrants say `the French' when they're referring to the whites, then we're lost. If their identity is located somewhere else and they're only in France for utilitarian reasons, then we're lost. I have to admit that the Jews are also starting to use this phrase. I hear them saying `the French' and I can't stand it. I say to them, `If for you France is a utilitarian matter, but your identity is Judaism, then be honest with yourselves: You have Israel.' This is really a bigger problem: We're living in a post-national society in which for everyone the state is just utilitarian, a big insurance company. This is an extremely serious development.

"But if they have a French identity card, then they're French. And if not, they have the right to go. They say, `I'm not French. I live in France and I'm also in a bad economic state.' No one's holding them here. And this is precisely where the lie begins. Because if it were the neglect and poverty, then they would go somewhere else. But they know very well that anywhere else, and especially in the countries from whence they came, their situation would be worse, as far as rights and opportunities go."

But the problem today is the integration into French society of young men and women who are from the third generation. This isn't a wave of new immigrants. They were born in France. They have nowhere to go.

"This feeling, that they are not French, isn't something they get from school. In France, as you perhaps know, even children who are in the country illegally are still registered for school. There's something surprising, something paradoxical, here: The school could call the police, since the child is in France illegally. Yet the illegality isn't taken into account by the school. So there are schools and computers everywhere, too. But then the moment comes when an effort must be made. And the people that are fomenting the riots aren't prepared to make this effort. Ever.

"Take the language, for example. You say they are third generation. So why do they speak French the way they do? It's butchered French - the accent, the words, the syntax. Is it the school's fault? The teachers' fault?"

Since the Arabs and blacks apparently have no intention of leaving France, how do you suggest that the problem be dealt with?

"This problem is the problem of all the countries of Europe. In Holland, they've been confronting it since the murder of Theo van Gogh. The question isn't what is the best model of integration, but just what sort of integration can be achieved with people who hate you."

And what will happen in France?

"I don't know. I'm despairing. Because of the riots and because of their accompaniment by the media. The riots will subside, but what does this mean? There won't be a return to quiet. It will be a return to regular violence. So they'll stop because there is a curfew now, and the foreigners are afraid and the drug dealers also want the usual order restored. But they'll gain support and encouragement for their anti-republican violence from the repulsive discourse of self-criticism over their slavery and colonization. So that's it: There won't be a return to quiet, but a return to routine violence."

So your worldview doesn't stand a chance anymore?

"No, I've lost. As far as anything relating to the struggle over school is concerned, I've lost. It's interesting, because when I speak the way I'm speaking now, a lot of people agree with me. Very many. But there's something in France - a kind of denial whose origin lies in the bobo, in the sociologists and social workers - and no one dares say anything else. This struggle is lost. I've been left behind."

http://www.haaretz.com/hasen/spages/646938.html ***

That interview is causing trouble. Please continue:

Sarkozy backs Finkielkraut over Muslim riot comments

By Daniel Ben Simon

The storm aroused by French-Jewish philosopher Alain Finkielkraut refuses to subside. On Sunday, French Interior Minister Nicolas Sarkozy threw his full weight behind the beleaguered philosopher, who has been forced to remain cloistered at home

following the sharp reactions to an interview he gave to Haaretz.

Speaking to reporters on Sunday, Sarkozy said: "Monsieur Finkielkraut is an intellectual who brings honor and pride to French wisdom ... If there is so much criticism of him, it might be because he says things that are correct."

The minister was asked about Finkielkraut because several reporters saw similarities between the conservative views the philosopher expressed about the recent riots in France and the tough stance the minister took in dealing with the agitators who took to the street night after night.

The liberal weekly Nouvel Observateur devoted its cover story to what it called "the new neo-reactionaries." Alongside Finkielkraut's picture on the cover was a title stating that Finkielkraut and his colleagues had worsened the social chasms in the country.

Others mentioned as supporters of similar ideas were Sarkozy, philosopher Andre Gluksman and historian Pierre-Andre Taguieff (who coined the phrase Judeophobia). They are described as belonging to a right-wing wave that is now prominent in France.

Sarkozy appeared ready to take on the media. He had been following the attacks on Finkielkraut for two weeks and was waiting for a suitable opportunity.

"What do you want of him?" he asked the media representatives. "M. Finkielkraut does not consider himself obliged to follow the monolithic thinking of many intellectuals, which led to Le Pen winning 24 percent in the elections. The philosophers who frequent the salons and live between Cafe de Flor and Boulevard St. Germain suddenly find that France no longer bears a resemblance to them."

This is an unprecedented attack on the left wing by the very person [Sarkosy] who is seen by many French as being the only one capable of preventing the disintegration of the republic.

The cafes and bistros of Boulevard St. Germain and the narrow alleyways of St. Germain-des-Pres were traditionally frequented by members of the left, led by Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, who would take their morning coffee and read the newspapers there. When the socialists came to power under Francois Mitterand in 1981, the celebrations there were legendary. But of late, the area has lost some of its left-wing color.

While Sarkozy has won popular support for his stronghanded policies, he has been criticized in the media for his autocratic manner and his lack of sympathy for the social causes behind the rioters' behavior. Finkielkraut appeared to be mouthing his words.

Finkielkraut's apologies printed in Le Monde, a few days after the Haaretz interview , disappointed many. His supporters felt he had retracted his words for fear of a media boycott, as had happened to others. As a result of his apologies, Finkielkraut was able to maintain his radio programs on the prestigious France Culture channel and the Jewish radio channel and even increased his audience.

The weekly Le Point also devoted a four-page report to the Finkielkraut affair this week. While the interviewees stressed his intellectual acumen, they almost all felt Finkielkraut had slipped up by mentioning the ethnic identity of the rioters - he had described them as blacks, Arabs and Muslims.

Nevertheless, to date, all the organizations and bodies that threatened to sue him for racism have changed their minds.

The trials of the rioters, however, will begin shortly. There are 785 detainees, of whom 83 are illegal residents. Seven will be deported in the next few days.

"They are on their way out," Sarkozy told the reporters.

http://www.haaretzdaily.com/hasen/spages/654370.html

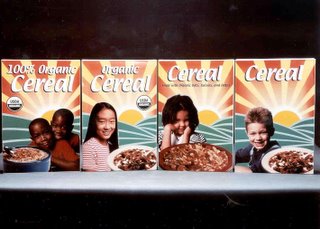

De Maistre, Burke, Hamann, Herder, Fichte; Walter Darre, Mircea Eliade, Rudolf Gorsleben, Franz Hartmann, Karl Haushofer, Martin Heidegger, CJ Jung, Georg Lanz von Liebnfels, Guido von List, Rudolf von Sebottendorff, Wolfram Sievers, Hermann Wirth; Barthes, Derrida, Foucault, Lyotard: These are names mostly unknown, some others known but unread; and they are the masters of our intellectual time, the movers and shakers of our thoughts on the nature of things in our time, the makers of our public opinions. They are some of the public intellectuals from whom we derive the concepts we have of identity, multi-culturalism, and ecology. Who'd have guessed? Most if not all are Nazis, and some are simply fascists. What does it say about us? How is it that we follow the very ideas of an ideology we hate violently and waged war to annihilate, and yet we hold dear many of the ideas they formulated? How can this be possible? How is it possible that 18th century reactionaries and 20th century Nazis have morphed into those who now foist upon the world the culture of philobarbarism and multi-cultural moral relativism? We'll look below at some of the recent origins of what's come about and why. Why, for example, the picture above turns us all into dewy-eyed sentimentalists cooing over the inclusive post-modernist beauty of our times even as we sink into a mire of suicidal cultural dhimmitude and generalized social self-hatred.

De Maistre, Burke, Hamann, Herder, Fichte; Walter Darre, Mircea Eliade, Rudolf Gorsleben, Franz Hartmann, Karl Haushofer, Martin Heidegger, CJ Jung, Georg Lanz von Liebnfels, Guido von List, Rudolf von Sebottendorff, Wolfram Sievers, Hermann Wirth; Barthes, Derrida, Foucault, Lyotard: These are names mostly unknown, some others known but unread; and they are the masters of our intellectual time, the movers and shakers of our thoughts on the nature of things in our time, the makers of our public opinions. They are some of the public intellectuals from whom we derive the concepts we have of identity, multi-culturalism, and ecology. Who'd have guessed? Most if not all are Nazis, and some are simply fascists. What does it say about us? How is it that we follow the very ideas of an ideology we hate violently and waged war to annihilate, and yet we hold dear many of the ideas they formulated? How can this be possible? How is it possible that 18th century reactionaries and 20th century Nazis have morphed into those who now foist upon the world the culture of philobarbarism and multi-cultural moral relativism? We'll look below at some of the recent origins of what's come about and why. Why, for example, the picture above turns us all into dewy-eyed sentimentalists cooing over the inclusive post-modernist beauty of our times even as we sink into a mire of suicidal cultural dhimmitude and generalized social self-hatred.